We’re leaving Kubernetes

Kubernetes seems like the obvious choice for building out remote, standardized and automated development environments. We thought so too and have spent six years invested in making the most popular cloud development environment platform at internet scale. That’s 1.5 million users, where we regularly see thousands of development environments per day. In that time, we’ve found that Kubernetes is not the right choice for building development environments.

This is our journey of experiments, failures and dead-ends building development environments on Kubernetes. Over the years, we experimented with many ideas involving SSDs, PVCs, eBPF, seccomp notify, TC and io_uring, shiftfs, FUSE and idmapped mounts, ranging from microVMs, kubevirt to vCluster.

In pursuit of the most optimal infrastructure to balance security, performance and interoperability. All while wrestling with the unique challenges of building a system to scale up, remain secure as it’s handling arbitrary code execution, and be stable enough for developers to work in.

This is not a story of whether or not to use Kubernetes for production workloads that’s a whole separate conversation. As is the topic of how to build a comprehensive soup-to-nuts developer experience for shipping applications on Kubernetes.

This is the story of how (not) to build development environments in the cloud.

UPDATE: Since publishing we’ve received a lot of questions [1] about what our post-kubernetes architecture looks like. There is a lot to cover so I recorded a deep-dive session. You can watch it here →

- Thanks for the interest and kind words, Chris (blog author)

Why are development environments unique?

Before we dive in, it’s crucial to understand what makes development environments unique compared to production workloads:

- They are extremely stateful and interactive: Which means they cannot be moved from one node to another. The many gigabytes of source code, build caches, Docker container and test data are subject to a high change rate and costly to migrate. Unlike many production services, there’s a 1-to-1 interaction between the developer and their environment.

- Developers are deeply invested in their source code and the changes they make: Developers don’t take kindly to losing any source code changes or to being blocked by any system. This makes development environments particularly intolerant to failure.

- They have unpredictable resource usage patterns: Development Environments have particular and unpredictable resource usage patterns. They won’t need much CPU bandwidth most of the time, but will require several cores within a few 100ms. Anything slower than that manifests as unacceptable latency and unresponsiveness.

- They require far-reaching permissions and capabilities: Unlike production workloads, development environments often need root access and the ability to download and install packages. What constitutes a security concern for production workloads, is expected behavior of development environments: getting root access, extended network capabilities and control over the system (e.g. mounting additional filesystems).

These characteristics set development environments apart from typical application workloads and significantly influence the infrastructure decisions we’ve made along the way.

The system today: obviously it’s Kubernetes

When we started Gitpod, Kubernetes seemed like the ideal choice for our infrastructure. Its promise of scalability, container orchestration, and rich ecosystem aligned perfectly with our vision for cloud development environments. However, as we scaled and our user base grew, we encountered several challenges around security and state management that pushed Kubernetes to its limits. Fundamentally, Kubernetes is built to run well controlled application workloads, not unruly development environments.

Managing Kubernetes at scale is complex. While managed services like GKE and EKS alleviate some pain points, they come with their own set of restrictions and limitations. We found that many teams looking to operate a CDE underestimate the complexity of Kubernetes, which lead to a significant support load for our previous self-managed Gitpod offering.

Resource management struggles

One of the most significant challenges we faced was resource management, particularly CPU and memory allocation per environment. At first glance, running multiple environments on a node seems attractive to share resources (such as CPU, memory, IO and network bandwidth) between those resources. In practice, this incurs significant noisy neighbor effects leading to a detrimental user experience.

CPU challenges

CPU time seems like the simplest candidate to share between environments. Most of the time development environments don’t need much CPU, but when they do, they need it quickly. Latency becomes immediately apparent to users when their language server starts to lag or their terminal becomes choppy. This spiky nature of the CPU requirements of development environments (periods of inactivity followed by intensive builds) makes it difficult to predict when CPU time is needed.

For solutions, we experimented with various CFS (Completely Fair Scheduler) based schemes, implementing a custom controller using a DaemonSet. A core challenge is that we can not predict when CPU bandwidth is needed, but only understand when it would have been needed (by observing nr_throttled of the cgroup’s cpu_stats).

Even when using static CPU resource limits, challenges arise, because unlike application workloads a development environment will run many processes in the same container. These processes compete for the same CPU bandwidth, which can lead to e.g. VS Code disconnects because VS Code server is starved for CPU time.

We have attempted to solve this problem by adjusting the process priorities of the individual processes, e.g. increasing the priority of bash or vscode-server. However, these process priorities apply to the entire process group (depending on your Kernel’s autogroup scheduling configuration), hence also to the resource hungry compilers started in a VS Code terminal. Using process priorities to counter terminal lag requires a carefully written control loop to be effective.

We introduced custom CFS and process priority based control loops built on cgroupv1 and moved to cgroupsv2 once they became more readily available on managed Kubernetes platforms with 1.24. Dynamic resource allocation introduced with Kubernetes 1.26 means one no longer needs to deploy a DaemonSet and modify cgroups directly, possibly at the expense of the control loop speed and hence effectiveness. All the schemes outlined above rely on second-by-second readjustment of CFS limits and niceness values.

Memory management

Memory management presented its own set of challenges. Assigning every environment a fixed amount of memory, so that under maximum occupation each environment gets their fixed share is straightforward, but very limiting. In the cloud, RAM is one of the more expensive resources, hence the desire to overbook memory.

Until swap-space became available in Kubernetes 1.22, memory overbooking was near impossible to do, because reclaiming memory inevitably means killing processes. With the addition of swap space the need to overbook memory has somewhat gone away, since swap works well in practice for hosting development environments.

Storage performance optimization

Storage performance is important for the startup performance and experience of development environments. We have found that specifically IOPS and latency affect experience within an environment. IO bandwidth however directly impacts your workspace startup performance, specifically when creating/restoring backups or extracting large workspace images.

We experimented with various setups to find the right balance between speed and reliability, cost and performance.

- SSD RAID 0: This offered high IOPS and bandwidth but tied the data to a specific node. The failure of any single disk would result in complete data loss. This is how gitpod.io operates today and we have not seen such a disk failure happen yet. A simpler version of this setup is to use a single SSD attached to the node. This approach provides lower IOPS and bandwidth, and still binds the data to individual nodes.

- Block storage such as EBS volumes or Google persistent disks which are permanently attached to the nodes considerably broaden the different instances or availability zones that can be used. While still bound to a single node, and offering considerably lower throughput/bandwidth than local SSDs they are more widely available.

- Persistent Volume Claims (PVCs) seem like the obvious choice when using Kubernetes. As abstraction over different storage implementations they offer a lot of flexibility, but also introduce new challenges:

- Unpredictable attachment and detachment timing, leading to unpredictable workspace startup times. Combined with increased scheduling complexity they make implementing effective scheduling strategies harder.

- Reliability issues leading to workspace failures, particularly during startup. This was especially noticeable on Google Cloud (in 2022) and rendered our attempts to use PVCs impractical.

- Limited number of disks that could be attached to an instance, imposing additional constraints on the scheduler and number of workspaces per node.

- AZ locality constraints which makes balancing workspaces across AZs even harder.

Backing up and restoring local disks proved to be an expensive operation. We implemented a solution using a daemonSet that uploads and downloads uncompressed tar archives to/from S3. This approach required careful balancing of I/O, network bandwidth, and CPU usage: for example, (de)compressing archives consumes most available CPU on a node, whereas the extra traffic produced by uncompressed backups usually doesn’t consume all available network bandwidth (if the number of concurrently starting/stopping workspaces is carefully controlled).

IO bandwidth on the node is shared across workspaces. We found that, unless we limited the IO bandwidth available to each workspace, other workspaces might starve for IO bandwidth and cease to function. Particularly the content backup/restore produced this problem. We implemented cgroup-based IO limiter which imposed fixed IO bandwidth limits per environment to solve this problem.

Autoscaling and startup time optimization

Our primary goal was to minimize startup time at all costs. Unpredictable wait times can significantly impact productivity and user satisfaction. However, this goal often conflicted with our desire to pack workspaces densely to maximize machine utilization.

We initially thought that running multiple workspaces on one node would help with startup times due to shared caches. However, this didn’t pan out as expected. The reality is that Kubernetes imposes a lower bound for startup time because of all the content operations that need to happen, content needs to be moved into place, which takes time.

Short of keeping workspaces in hot standby (which would be prohibitively expensive), we had to find other ways to optimize startup times.

Scaling ahead: evolution of our approach

To minimize startup time, we explored various approaches to scale up and ahead:

- Ghost workspaces: Before cluster autoscaler plugins were available, we experimented with “ghost workspaces”. These were preemptible pods that occupied space to scale ahead. We implemented this using a custom scheduler. However, this approach proved to be slow and unreliable to replace.

- Ballast pods: An evolution of the ghost workspace concept, ballast pods filled an entire node. This resulted in less replacement cost and faster replacement times compared to ghost workspaces.

- Autoscaler plugins: In June 2022, we switched to using cluster-autoscaler plugins when they were introduced. With these plugins we no longer needed to “trick” the autoscaler, but could directly affect how scale-up happens. This marked a significant improvement in our scaling strategy.

Proportional autoscaling for peak loads

To handle peak loads more effectively, we implemented a proportional autoscaling system. This approach controls the rate of scale-up as a function of the rate of starting development environments. It works by launching empty pods using the pause image, allowing us to quickly increase our capacity in response to demand spikes.

Image pull optimization: a tale of many attempts

Another crucial aspect of startup time optimization was improving image pull times. Workspace container images (i.e. all the tools available to a developer) can grow to more than 10 gigabytes uncompressed. Downloading and extracting this amount of data for every workspace considerably taxes a node’s resources. We explored numerous strategies to speed up image pulls:

- Daemonset pre-pull: We tried pre-pulling common images using a daemonSet. However, this proved ineffective during scale-up operations because when the node came online, and workspaces were starting, the images still wouldn’t be present on the node. Also, the pre-pulls would now compete for IO and CPU bandwidth with the starting workspaces.

- Layer reuse maximization: We built our own images using a custom builder called dazzle, which can build layers independently. This approach aimed to maximize layer reuse. However, we found that layer reuse is very difficult to observe due to the high cardinality and amount of indirections in the OCI manifests.

- Pre-baked images: We experimented with baking images into the node disk image. While this improved startup times, it had significant drawbacks. The images quickly became outdated, and this approach didn’t work for self-hosted installations.

- Stargazer and lazy-pulling: This method required all images to be converted, which added complexity, cost, and time to our operations. Additionally, not all registries supported this approach when we tried it in 2022.

- Registry-facade + IPFS: This solution worked well in practice, providing good performance and distribution. We gave a KubeCon talk about this approach in 2022. However, it introduced significant complexity to our system.

There is no one-size-fits all solution for image caching, but a set of trade-offs with respect to complexity, cost and restrictions imposed on users (images they can use). We have found that homogeneity of workspace images is the most straightforward way to optimize startup times.

Networking complexities

Networking in Kubernetes introduced its own set of challenges, specifically:

Development environment access control: by default the network of environments needs to be entirely isolated from one another, i.e. one environment cannot reach another. The same is true for the access of a user to the workspace. Network Policies go a long way in ensuring environments are properly disconnected from each other.

Initially we controlled the access to individual environment ports (such as the IDE, or services running in the workspace) using Kubernetes services, together with an ingress proxy that would forward traffic to the service, resolving it using DNS. This quickly became unreliable at scale because of the sheer number of services. Name resolution would fail, and if not careful (e.g. setting enableServiceLinks: false) one can bring entire workspaces down.

Network bandwidth sharing on the node is yet another resource that needs to be shared with multiple workspaces on a single node. Some CNIs offer network shaping support (e.g. Cilium’s Bandwidth Manager). This now leaves you with yet another resource to control for, and potentially share between environments.

Security and isolation: balancing flexibility and protection

One of the most significant challenges we faced in our Kubernetes-based infrastructure was providing a secure environment while giving users the flexibility they need for development. Users want the ability to install additional tools (e.g., using apt-get install), run Docker, or even set up a Kubernetes cluster within their development environment. Balancing these requirements with robust security measures proved to be a complex undertaking.

The naive approach: root access

The simplest solution would be to give users root access to their containers. However, this approach quickly reveals its flaws:

- Giving users root access essentially provides them with root privileges on the node itself, granting access to the development environment platform and other development environments that are running on that node .

- This eliminates any meaningful security boundary between users and the host system meaning developers can accidentally, or intentionally interfere and break the development environment platform itself or even access others’ development environments.

- It also exposes the infrastructure to potential abuse and security risks. It is then also not possible to implement a true access control model and the architecture falls short of zero-trust. You cannot ensure that a given actor in the system performing an action was verifiably themselves.

Clearly, a more sophisticated approach was needed.

User namespaces: a more nuanced solution

To address these challenges, we turned to user namespaces, a Linux kernel feature that provides fine-grained control over the mapping of user and group IDs inside containers. This approach allows us to give users “root-like” privileges within their container without compromising the security of the host system.

While Kubernetes introduced support for user namespaces in version 1.25, we had already implemented our own solution starting with Kubernetes 1.22. Our implementation involved several complex components:

Filesystem UID shift: This is necessary to ensure that files created inside the container map correctly to UIDs on the host system. We experimented with several approaches:

- We continue to use shiftfs as our primary method for filesystem UID shifting. Despite being deprecated in some contexts, shiftfs still provides the functionality we need with acceptable performance characteristics.

- We’ve experimented with fuse-overlayfs, which provided the necessary functionality but had performance limitations.

- While idmapped mounts offer potential benefits, we haven’t transitioned to them yet due to various compatibility and implementation considerations.

Mounting masked proc: When a container starts, it typically wants to mount /proc. However, in our security model, /proc is sensibly masked to prevent potential security bypasses. Working around this limitation required a tricky solution:

- We construct a masked proc filesystem.

- This masked proc is then moved into the correct mount namespace.

- We implement this using seccomp notify, which allows us to intercept and modify certain system calls.

FUSE support: Adding FUSE (Filesystem in Userspace) support, which is crucial for many development workflows, required implementing custom device policies. This involved modifying the container’s eBPF (extended Berkeley Packet Filter) device filter, a low-level programming capability that allows us to make fine-grained decisions about device access.

Network capabilities: As true root one holds the CAP_NET_ADMIN and CAP_NET_RAW capabilities which provide far-reaching privileges to configure networking. Container runtimes (such as Docker/runc) make extensive use of these capabilities. Granting such capabilities to the development environment container would interfere with CNI and break the security isolation.

To provide such capabilities we ended up creating another network namespace inside the Kubernetes container, first connected to the outside world using slirp4netns and later using a veth pair and custom and nftables rules.

Enabling docker: required some specific hacks for Docker itself. We register a custom runc-facade which modifies the OCI runtime spec produced by Docker. This lets us remove e.g. OOMScoreAdj which still isn’t allowed because that would require CAP_SYS_ADMIN on the node.

Implementing this security model came with its own set of challenges:

- Performance impact: Some of our solutions, particularly earlier ones like fuse-overlayfs, had noticeable performance impacts. We’ve continually worked to optimize these.

- Compatibility: Not all tools and workflows are compatible with this restricted environment. We’ve had to carefully balance security with usability.

- Complexity: The resulting system is significantly more complex than a simple containerized environment, which impacts both development and operational overhead.

- Keeping up with Kubernetes: As Kubernetes has evolved, we’ve had to adapt our custom implementations to take advantage of new features while maintaining backwards compatibility.

The micro-VM experiment

As we grappled with the challenges of Kubernetes, we began exploring micro-VM (uVM) technologies like Firecracker, Cloud Hypervisor, and QEMU as a potential middle ground. This exploration was driven by the promise of improved resource isolation, compatibility with other workloads (e.g. Kubernetes) and security, while potentially maintaining some of the benefits of containerization.

The promise of micro-VMs

Micro-VMs offered several enticing benefits that aligned well with our goals for cloud development environments:

- Enhanced resource isolation: uVMs promised better resource isolation compared to containers, albeit at the expense of overbooking capabilities. With uVMs, we would no longer have to contend with shared kernel resources, potentially leading to more predictable performance for each development environment.

- Memory snapshots and fast resume: One of the most exciting features, particularly with Firecracker using userfaultfd, was the support for memory snapshots. This technology promised near-instant full machine resume, including running processes. For developers, this could mean significantly faster environment startup times and the ability to pick up exactly where they left off.

- Improved security boundaries: uVMs offered the potential to serve as a robust security boundary, potentially eliminating the need for the complex user namespace mechanisms we had implemented in our Kubernetes setup. This could provide full compatibility with a wider range of workloads, including nested containerization (running Docker or even Kubernetes within the development environment).

Challenges with micro-VMs

However, our experiments with micro-VMs revealed several significant challenges:

- Overhead: Even as lightweight VMs, uVMs introduced more overhead than containers. This impacted both performance and resource utilization, key considerations for a cloud development environment platform.

- Image conversion: Converting OCI (Open Container Initiative) images into uVM-consumable filesystems required custom solutions. This added complexity to our image management pipeline and potentially impacted startup times.

- Technology-specific limitations:

- Firecracker:

- Lack of GPU support, which is increasingly important for certain development workflows.

- No virtiofs support at the time of our experiments (mid 2023), limiting our options for efficient file system sharing.

- Cloud hypervisor:

- Slower snapshot and restore processes due to the lack of userfaultfd support, negating one of the key advantages we hoped to gain from uVMs.

- Firecracker:

- Data movement challenges: Moving data around became even more challenging with uVMs, as we now had to contend with large memory snapshots. This affected both scheduling and startup times, two critical factors for user experience in cloud development environments.

- Storage considerations: Our experiments with attaching EBS volumes to micro-VMs opened up new possibilities but also raised new questions:

- Persistent storage: Keeping workspace content on attached volumes reduced the need to pull data from S3 repeatedly, potentially improving startup times and reducing network usage.

- Performance considerations: While sharing high-throughput volumes among workspaces showed promise for improving I/O performance, it also raised concerns about implementing effective quotas, managing latency, and ensuring scalability.

Lessons from the uVM experiment

While micro-VMs didn’t ultimately become our primary infrastructure solution, the experiment provided valuable insights:

- We loved the experience of full workspace backup and runtime state suspend/resume provided for development environments.

- We, for the first time, considered moving away from Kubernetes. The effort to integrate KVM and uVMs into pods had us explore options outside of Kubernetes.

- We, once again, identified storage as the crucial element for providing all three: reliable startup performance, reliable workspaces (don’t lose my data) and optimal machine utilization.

Kubernetes is immensely challenging as a development environment platform

As I mentioned at the beginning, for development environments we need a system that respects the uniquely stateful nature of development environments. We need to give the necessary permissions for developers to be productive, whilst ensuring secure boundaries. And we need to do all of this whilst keeping operational overhead low and not compromising security.

Today, achieving all of the above with Kubernetes is possible—but comes at a significant cost. We learned the difference between application and system workloads the hard way.

Kubernetes is incredible. It’s supported by an engaged and passionate community, which builds a truly rich ecosystem. If you’re running application workloads, Kubernetes continues to be a fine choice. However for system workloads like development environments Kubernetes presents immense challenges in both security and operational overhead. Micro-VMs and clear resource budgets help, but make cost a more dominating factor.

So after many years of effectively reverse-engineering and forcing development environments onto the Kubernetes platform we took a step back to think about what we believe a future development architecture needs to look like. In January 2024 we set out to build it. In October, we shipped it: Gitpod Flex.

More than six years of incredibly hard-won insights for running development environments securely at internet scale went into the architectural foundations.

The future of development environments

In Gitpod Flex we carried over the foundational aspects of Kubernetes such as the liberal application of control theory and the declarative APIs whilst simplifying the architecture and improving the security foundation.

We orchestrate development environments using a control plane heavily inspired by Kubernetes. We introduced some necessary abstraction layers that are specific to development environments and cast aside much of the infrastructure complexity that we didn’t need—all whilst putting zero-trust security first.

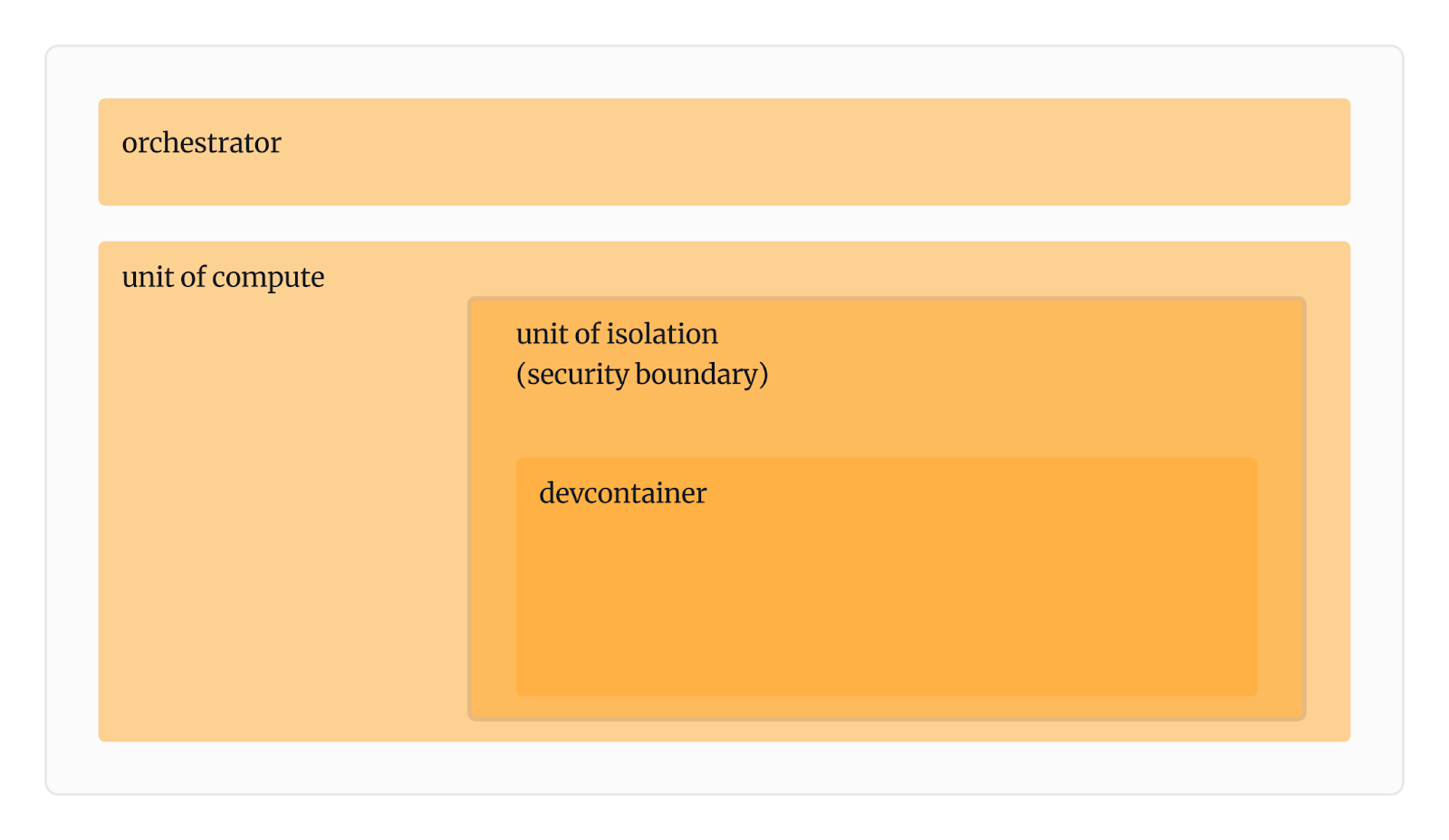

Caption: Security boundaries of Gitpod Flex.

This new architecture allows us to integrate devcontainer seamlessly. We also unlocked the ability to run development environments on your desktop. Now that we’re no longer carrying the heavy weight of the Kubernetes platform, Gitpod Flex can be deployed self-hosted in less than three minutes and in any number of regions, giving more fine-grained control on compliance and added flexibility when modeling organizational boundaries and domains.

We’ll be posting a lot more about Gitpod Flex architecture in the coming weeks or months. I’d love to invite you on November the 6th to a virtual event where I’ll be giving a demo of Gitpod Flex and I’ll deep-dive into the architecture and security model at length. You can sign-up here.

When it comes to building a platform for standardized, automated and secure development environments choose a system because it improves your developer experience, eases your operational burden and improves your bottom line. You are not choosing Kubernetes vs something else, you are choosing a system because it improves the experience for the teams you support.

UPDATE: Since publishing we’ve received a lot of questions [1] about what our post-kubernetes architecture looks like. There is a lot to cover so I recorded a deep-dive session. You can watch it here →

- Thanks for the interest and kind words, Chris (blog author)